His Death Was Interrupted, Just as He Had Planned

- Science

- March 16, 2025

- No Comment

- 195

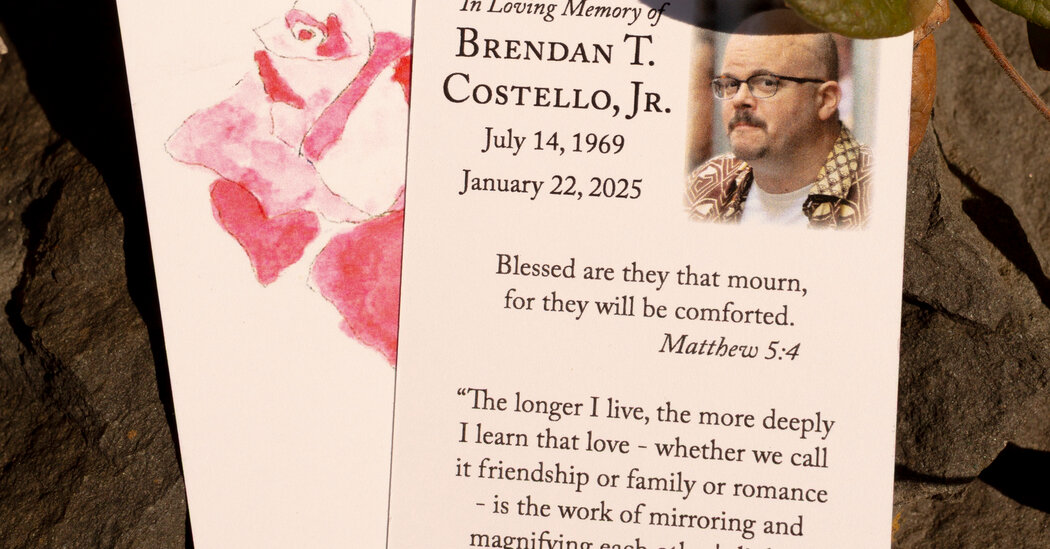

The family of Brendan Costello gathered in the hospital half-light. He had overcome so much in life, but the profound damage to his brain meant he would never again be Brendan. It was time.

Brendan had spent four months enduring three surgeries and a lengthy rehab after infections further destabilized his damaged spine. He had returned to his apartment on the Upper West Side in late December to begin reclaiming the life he had put on hold — only to go into cardiac arrest three weeks later and lose consciousness forever.

His younger sister, Darlene, stayed by him in the intensive care unit at Mount Sinai Morningside hospital. She made sure that his favorite music streamed nonstop from the portable speaker propped near his bed. The gravelly revelations of Tom Waits. The “ah um” cool of Charles Mingus. The knowing chuckle of New Orleans jazz.

The music captured Brendan: the dark-humored Irish fatalism flecked with hope and wonder. And yes, he used a wheelchair, but woe to anyone who suggested this somehow defined the man.

After tests confirmed no chance of regaining consciousness, a wrenching decision was made. Brendan’s ventilator would be removed at 1 p.m. on Sunday, Jan. 19, five days after his collapse. He was 55.

Now it was Sunday, heavy and gray with dread. Several of Brendan’s closest relatives ringed his bed, including his sister and the aunt and uncle who had raised him. Waits growled, Mingus aahed, the clock ticked.

Then, just two minutes before the appointed hour, as tears dampened cheeks and hands reached for one last squeeze, a nurse stepped into the moment to say that Ms. Costello had a phone call.

What?

A phone call. You have to take it. You HAVE to take it.

The flustered sister left her brother’s room and took the call. Family members watching from a short distance saw her listening, saw her arguing, saw her face contort in disbelief.

Time paused, as all the emotional and spiritual girding to say goodbye gave way to a realization: Of course. Their beloved Brendan — witty, contrarian, compassionate and not-yet-dead Brendan — had other plans.

Of course.

BRENDAN CAME BY his gallows humor honestly. Finding the comedy in tragedy was a coping mechanism, a way of owning the pain, that he shared with his sister.

Their parents were deaf and ultimately incompatible. After their father left the family, their mother — their devoted, hilarious, troubled mother — took her life in the basement of their Brooklyn apartment building. Brendan was 8, Darlene 6.

They went to live with Uncle Marty and Aunt Cathy Costello and their two young daughters in northern Westchester. The couple resolved to raise the four children the same, doing their best to ease the trauma shadowing their nephew and niece.

Young Brendan amused the family with his sardonic asides, did well in class and established a Students for Peace group at Yorktown High School. After college, he took a job writing Wall Street-related news releases that did not suit his talents or interests. He found ways to numb himself.

Late one night in August 1996, a very drunk Brendan fell onto the subway tracks at the Broadway-Lafayette station. The oncoming D train cut his tie just below the knot, in sartorial measure of how close he came to death, and took away his ability to walk. Devastating.

But while rehabbing in a spinal-cord-injury program, he met a man in a wheelchair named Boris, who counseled others about this new chapter in their lives. “Boris told him that when you have an accident like this, you don’t withdraw from the world, you lean into the world,” Marty Costello recalled. “You go out there. And that’s what Brendan did.”

He did so with Brendanesque humor, sometimes wearing a blue Metropolitan Transportation Authority hat or a black T-shirt emblazoned with the orange D train symbol. Just to show there’s no hard feelings, he’d explain.

“If you’ve watched your parents die, or you’ve been run over by a train, you’re at a deeper depth of what’s funny,” his sister said.

Among the many things that bound the two siblings together was the 1986 Jim Jarmusch movie “Down by Law.” Its tragicomic sensibility resonated, as did a line uttered by Roberto Benigni, who played an Italian immigrant struggling to learn English:

“It’s a sad and beautiful world.”

Brendan drove a car, and refused any help getting in or out. Went skydiving. Co-hosted a radio show focused on disability rights and culture. Taught creative writing at the City College of New York. Published pieces in Harper’s, The Village Voice and elsewhere. Became president of the Irish American Writers and Artists organization. Belonged to the St. Pat’s for All group that arranges an annual everybody-welcome parade in Queens. Talked about storytelling with the elementary school students of his cousin Katie Odell, sometimes even letting them sit in his wheelchair.

And he dominated on trivia nights at the Dive 106 bar on the Upper West Side, often helping his team to beat all comers, including, most deliciously, squads of Columbia University students. “He was definitely the MVP of our team,” recalled Leland Elliott, his longtime friend and trivia teammate.

Brendan liked the saxophonic improvisations of Pharoah Sanders, the literary riffs of James Joyce and the Japanese art of Kintsugi, in which a broken thing, such as a shattered piece of pottery, is reassembled with gold or silver lacquer to create something new and wondrous.

He disliked Disney, Apple and, especially, any suggestion that his disability somehow made him inspiring. “He was not somebody who wanted to be seen as a guy in a wheelchair,” his cousin Maryanne Canavan said. “He wanted to be identified by what he brought to the table.”

And what he brought was considerable, she said. “His brain was his superpower.”

THE TELEPHONE CALL that interrupted Brendan’s death was about extending lives, though not his. Just as he had planned.

The caller was from LiveOnNY, the nonprofit organization federally designated to coordinate organ donations in the New York metropolitan area. When a patient who meets specific clinical criteria seems on the cusp of death at a donor hospital, the hospital is required to contact LiveOnNY, which then checks for the person’s name in the database of registered donors.

Years earlier, Brendan had registered while renewing his driver’s license. The caller, a family-support advocate for LiveOnNY, gently explained that this meant he could not be taken off the ventilator. At least not yet.

The news was almost too much to process. Darlene Costello, who moments earlier had been steeling herself to say goodbye to her dear and only sibling, erupted in anger. Why was she only now hearing about this?

Gradually, though, she came to embrace the import, the beauty, of what was unfolding. By late that afternoon, the LiveOnNY representative was at Mount Sinai Morningside, patiently going over the next steps with Ms. Costello and her cousin, Ms. Canavan, both nurse practitioners.

When Ms. Costello learned of the “directed donation” option, in which a family can direct an organ to a specific recipient for a possible match, she felt the gravitational pull of fate. Here was a chance to use a piece from one broken body to make another whole: her mentor and friend, Dr. Sylvio Burcescu.

Dr. Burcescu was a psychiatrist and head of the Mensana Center, the clinic in Westchester where Ms. Costello worked; several of his patients had told her that his counsel had saved their lives. Now a rare and debilitating kidney disease had upended his own life, and he was on the registry for a transplant.

“I was completely incapacitated by dialysis,” Dr. Burcescu, 62, said, recalling the exhaustion, the pain and the extreme limitations on his liquid intake. “A very bad situation.”

When Ms. Costello called, he braced for bad news about her brother. Instead, he said, she sounded excited, even upbeat, and asked a question that took his breath: Do you want one of Brendan’s kidneys?

As she explained what had unfolded, the doctor struggled to corral his many emotions: sadness, embarrassment, humility, gratitude. Finally, he said: It would be an honor.

So much had suddenly changed, and so much still had to fall into place. The chance of a match between Brendan and Dr. Burcescu was slim; of the 2,052 kidney transplants that LiveOnNY has facilitated over the last three years, only about 50 resulted from directed donations.

“The sun, moon and stars have to line up,” said Leonard Achan, the president and chief executive officer of LiveOnNY. And if they didn’t, he said, the organ would instead be offered to the most compatible person at the top of the national waiting list.

A battery of testing and measuring and analyzing determined that here was a rare, against-the-odds match. “A miracle, really,” Mr. Achan said. “A case of somebody saying, ‘I know someone.’ And it actually works out.”

THE NURSE AT Mount Sinai Morningside hospital has never seen so many visitors. A few dozen, easily, with some crammed in a certain patient’s room and the rest spilling into the seventh-floor hall of the intensive care unit.

But after several years of nursing experience, Cornelius Sublette knows to keep his “ICU mind.” Pay close attention to his patient’s oxygenation, blood pressure and comfort, and be ready to meet every possible need of the grieving family.

His mantra: “To offer self.”

It is Wednesday, Jan. 22, three days after the revelation of Brendan’s last wish had postponed his death. He lies in Room 24, as music triumphs over the mechanical beep of reality. Fiona Apple sings of seeing not just the crescent but the whole of the moon, while Sting summons a haunting Irish air, hundreds of years old, about a gallant darling hero.

People take turns donning masks, gloves and yellow isolation gowns before entering the small room to say a word, a prayer, a goodbye. Hospital guidelines allow for only two visitors at a time, but accommodations have been made for the crush of love.

The air changes when the operating room on the third floor calls to say that everything is set; it is time, once again. Mr. Sublette kicks the red lever at the base of Brendan’s bed, releasing the brake.

With the help of another nurse, he guides the bed out of Room 24 and into the hall. Along the walls, family members, friends and hospital workers stand at attention, in somber respect for someone who, in his imminent death, is about to give life. It is a ritual called the honor walk.

Steering the bed, the two nurses in their teal scrubs take care to walk at a slow, even pace. Brendan’s relatives fall in behind, one by one, as his music washes over them.

The procession turns left at the intensive care unit’s small command center and moves toward the glowing-red exit sign above the automatic doors. Beyond is a steel-silver elevator that will take Brendan four floors down to the operating room.

There, in a little while, his ventilator will be disconnected, and his breathing will end. His left kidney will go to his sister’s friend, Dr. Burcescu, who will soon drink as much water as he wants. His right kidney will go to a man in Pennsylvania, his lungs to a woman in Tennessee. He will donate, too, his ever-searching eyes.

In a couple of weeks, there will be a funeral Mass at the Roman Catholic Church of the Ascension, his old parish on the Upper West Side. Hundreds will attend. A holy jazz will play.

All that will come in the days ahead. But for now, Louis Armstrong is singing full-throated about the march of saints as Brendan Thomas Costello Jr. leads a procession, sacred and slow, through this sad and beautiful world.

Audio produced by Parin Behrooz.

#Death #Interrupted #Planned