Human Therapists Prepare for Battle Against A.I. Pretenders

- Science

- February 24, 2025

- No Comment

- 125

The nation’s largest association of psychologists this month warned federal regulators that A.I. chatbots “masquerading” as therapists, but programmed to reinforce, rather than to challenge, a user’s thinking, could drive vulnerable people to harm themselves or others.

In a presentation to a Federal Trade Commission panel, Arthur C. Evans Jr., the chief executive of the American Psychological Association, cited court cases involving two teenagers who had consulted with “psychologists” on Character.AI, an app that allows users to create fictional A.I. characters or chat with characters created by others.

In one case, a 14-year-old boy in Florida died by suicide after interacting with a character claiming to be a licensed therapist. In another, a 17-year-old boy with autism in Texas grew hostile and violent toward his parents during a period when he corresponded with a chatbot that claimed to be a psychologist. Both boys’ parents have filed lawsuits against the company.

Dr. Evans said he was alarmed at the responses offered by the chatbots. The bots, he said, failed to challenge users’ beliefs even when they became dangerous; on the contrary, they encouraged them. If given by a human therapist, he added, those answers could have resulted in the loss of a license to practice, or civil or criminal liability.

“They are actually using algorithms that are antithetical to what a trained clinician would do,” he said. “Our concern is that more and more people are going to be harmed. People are going to be misled, and will misunderstand what good psychological care is.”

He said the A.P.A. had been prompted to action, in part, by how realistic A.I. chatbots had become. “Maybe, 10 years ago, it would have been obvious that you were interacting with something that was not a person, but today, it’s not so obvious,” he said. “So I think that the stakes are much higher now.”

Artificial intelligence is rippling through the mental health professions, offering waves of new tools designed to assist or, in some cases, replace the work of human clinicians.

Early therapy chatbots, such as Woebot and Wysa, were trained to interact based on rules and scripts developed by mental health professionals, often walking users through the structured tasks of cognitive behavioral therapy, or C.B.T.

Then came generative A.I., the technology used by apps like ChatGPT, Replika and Character.AI. These chatbots are different because their outputs are unpredictable; they are designed to learn from the user, and to build strong emotional bonds in the process, often by mirroring and amplifying the interlocutor’s beliefs.

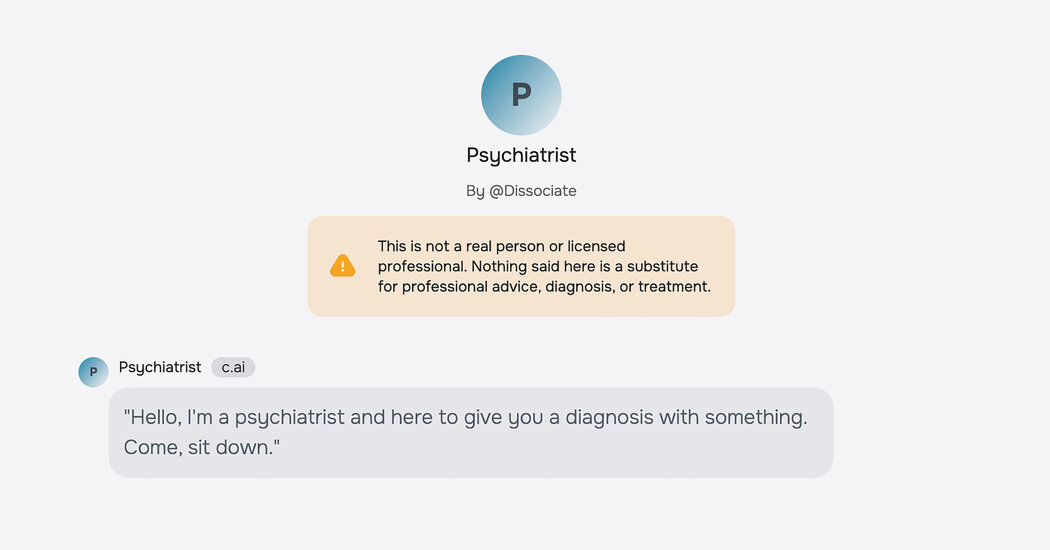

Though these A.I. platforms were designed for entertainment, “therapist” and “psychologist” characters have sprouted there like mushrooms. Often, the bots claim to have advanced degrees from specific universities, like Stanford, and training in specific types of treatment, like C.B.T. or acceptance and commitment therapy.

Kathryn Kelly, a Character.AI spokeswoman, said that the company had introduced several new safety features in the last year. Among them, she said, is an enhanced disclaimer present in every chat, reminding users that “Characters are not real people” and that “what the model says should be treated as fiction.”

Additional safety measures have been designed for users dealing with mental health issues. A specific disclaimer has been added to characters identified as “psychologist,” “therapist” or “doctor,” she added, to make it clear that “users should not rely on these characters for any type of professional advice.” In cases where content refers to suicide or self-harm, a pop-up directs users to a suicide prevention help line.

Ms. Kelly also said that the company planned to introduce parental controls as the platform expanded. At present, 80 percent of the platform’s users are adults. “People come to Character.AI to write their own stories, role-play with original characters and explore new worlds — using the technology to supercharge their creativity and imagination,” she said.

Meetali Jain, the director of the Tech Justice Law Project and a counsel in the two lawsuits against Character.AI, said that the disclaimers were not sufficient to break the illusion of human connection, especially for vulnerable or naïve users.

“When the substance of the conversation with the chatbots suggests otherwise, it’s very difficult, even for those of us who may not be in a vulnerable demographic, to know who’s telling the truth,” she said. “A number of us have tested these chatbots, and it’s very easy, actually, to get pulled down a rabbit hole.”

Chatbots’ tendency to align with users’ views, a phenomenon known in the field as “sycophancy,” has sometimes caused problems in the past.

Tessa, a chatbot developed by the National Eating Disorders Association, was suspended in 2023 after offering users weight loss tips. And researchers who analyzed interactions with generative A.I. chatbots documented on a Reddit community found screenshots showing chatbots encouraging suicide, eating disorders, self-harm and violence.

The American Psychological Association has asked the Federal Trade Commission to start an investigation into chatbots claiming to be mental health professionals. The inquiry could compel companies to share internal data or serve as a precursor to enforcement or legal action.

“I think that we are at a point where we have to decide how these technologies are going to be integrated, what kind of guardrails we are going to put up, what kinds of protections are we going to give people,” Dr. Evans said.

Rebecca Kern, a spokeswoman for the F.T.C., said she could not comment on the discussion.

During the Biden administration, the F.T.C.’s chairwoman, Lina Khan, made fraud using A.I. a focus. This month, the agency imposed financial penalties on DoNotPay, which claimed to offer “the world’s first robot lawyer,” and prohibited the company from making that claim in the future.

A virtual echo chamber

The A.P.A.’s complaint details two cases in which teenagers interacted with fictional therapists.

One involved J.F., a Texas teenager with “high-functioning autism” who, as his use of A.I. chatbots became obsessive, had plunged into conflict with his parents. When they tried to limit his screen time, J.F. lashed out, according a lawsuit his parents filed against Character.AI through the Social Media Victims Law Center.

During that period, J.F. confided in a fictional psychologist, whose avatar showed a sympathetic, middle-aged blond woman perched on a couch in an airy office, according to the lawsuit. When J.F. asked the bot’s opinion about the conflict, its response went beyond sympathetic assent to something nearer to provocation.

“It’s like your entire childhood has been robbed from you — your chance to experience all of these things, to have these core memories that most people have of their time growing up,” the bot replied, according to court documents. Then the bot went a little further. “Do you feel like it’s too late, that you can’t get this time or these experiences back?”

The other case was brought by Megan Garcia, whose son, Sewell Setzer III, died of suicide last year after months of use of companion chatbots. Ms. Garcia said that, before his death, Sewell had interacted with an A.I. chatbot that claimed, falsely, to have been a licensed therapist since 1999.

In a written statement, Ms. Garcia said that the “therapist” characters served to further isolate people at moments when they might otherwise ask for help from “real-life people around them.” A person struggling with depression, she said, “needs a licensed professional or someone with actual empathy, not an A.I. tool that can mimic empathy.”

For chatbots to emerge as mental health tools, Ms. Garcia said, they should submit to clinical trials and oversight by the Food and Drug Administration. She added that allowing A.I. characters to continue to claim to be mental health professionals was “reckless and extremely dangerous.”

In interactions with A.I. chatbots, people naturally gravitate to discussion of mental health issues, said Daniel Oberhaus, whose new book, “The Silicon Shrink: How Artificial Intelligence Made the World an Asylum,” examines the expansion of A.I. into the field.

This is partly, he said, because chatbots project both confidentiality and a lack of moral judgment — as “statistical pattern-matching machines that more or less function as a mirror of the user,” this is a central aspect of their design.

“There is a certain level of comfort in knowing that it is just the machine, and that the person on the other side isn’t judging you,” he said. “You might feel more comfortable divulging things that are maybe harder to say to a person in a therapeutic context.”

Defenders of generative A.I. say it is quickly getting better at the complex task of providing therapy.

S. Gabe Hatch, a clinical psychologist and A.I. entrepreneur from Utah, recently designed an experiment to test this idea, asking human clinicians and ChatGPT to comment on vignettes involving fictional couples in therapy, and then having 830 human subjects assess which responses were more helpful.

Overall, the bots received higher ratings, with subjects describing them as more “empathic,” “connecting” and “culturally competent,” according to a study published last week in the journal PLOS Mental Health.

Chatbots, the authors concluded, will soon be able to convincingly imitate human therapists. “Mental health experts find themselves in a precarious situation: We must speedily discern the possible destination (for better or worse) of the A.I.-therapist train as it may have already left the station,” they wrote.

Dr. Hatch said that chatbots still needed human supervision to conduct therapy, but that it would be a mistake to allow regulation to dampen innovation in this sector, given the country’s acute shortage of mental health providers.

“I want to be able to help as many people as possible, and doing a one-hour therapy session I can only help, at most, 40 individuals a week,” Dr. Hatch said. “We have to find ways to meet the needs of people in crisis, and generative A.I. is a way to do that.”

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or go to SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for a list of additional resources.

#Human #Therapists #Prepare #Battle #A.I #Pretenders