Trump’s efforts with DOGE cuts test Watergate-era reforms : NPR

- Politics

- February 15, 2025

- No Comment

- 112

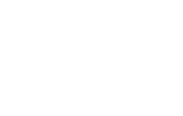

In this Nov. 17, 1973 file photo, President Richard Nixon speaks near Orlando, Fla. to the Associated Press Managing Editors annual meeting. Nixon told the APME “I am not a crook.”

File/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

File/AP

President Trump is firing government watchdogs, trying to shutter entire agencies and pausing spending on things that don’t fit with his agenda. These efforts to reshape the government at a rapid clip have put him on a collision course with laws passed after the Watergate scandal.

For a generation, the narrative was that Watergate ushered in greater congressional oversight and a taming of presidential power. But over the years, those limits spurred a movement on the political right to restore power in the executive branch, said Bruce Schulman, a history professor at Boston University.

Trump, in his second term, is pushing new boundaries. “What we are seeing now is a final campaign, a frontal attack of the last vestiges of that particular post-Nixon historical moment,” said Schulman.

President Richard Nixon at the White House with his family after his resignation on Aug. 9, 1974.

Keystone/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

hide caption

toggle caption

Keystone/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

What happened after Nixon

President Richard Nixon weaponized the FBI and CIA against his political enemies, resisted the will of Congress on federal spending and obstructed investigations into his alleged wrongdoing. Ultimately, he resigned as an impeachment effort was gaining steam.

“Nixon’s removal from office in 1974 initiated a widespread and bipartisan effort to limit presidential power, to clean up corruption, to make the government more transparent,” Schulman said.

Democratic Senator Walter Mondale was part of a bipartisan push to curb what he described as “the imperial presidency” in a 1974 interview with Newsportu.

“If we can — before this is over — establish the principle that any president including this one is under the law and must respond to the Constitution and the courts and to the Congress and the American people, we will have saved ourselves from a very dangerous trend,” Mondale said in the interview.

Watergate created an appetite for change

After Nixon’s resignation, a new class of lawmakers swept into Congress with a mandate for reform. They worked on a wide-ranging list of new checks on the executive branch. The laws sought to rein in presidential use of national emergencies and war powers.

There were new protections to prevent the federal civil service from being politicized and a new 10-year term for the FBI director to limit political interference.

The laws placed inspectors general in federal agencies, and created the Office of Government Ethics and the Office of Special Counsel — watchdogs to keep an eye on the executive branch.

“These are a bunch of laws that are meant to serve as notice of congressional intent, to stand up to presidential overreach,” said Andrew Rudalevige, a professor of government at Bowdoin College.

President Trump signs an executive action on tariffs in the Oval Office on Feb. 13, 2025.

Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP

hide caption

toggle caption

Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP

What Trump has been unwinding

Since taking office, Trump has fired more than a dozen inspectors general. He also blew past a 2022 law requiring that there be cause for any such firings and provide advance notice to congress.

“As the statute is written … what President Trump did, violates the law,” said Stanford law professor Anne Joseph O’Connell. “Now, whether this conservative Supreme Court would uphold that law is uncertain.”

The White House is arguing that because these watchdogs work in the executive branch, President Trump has the authority to fire them no matter what the laws written by Congress say.

“Those are plausible legal arguments,” said Blake Emerson at UCLA Law. “They were not plausible legal arguments 20 years ago — but they are now.”

Federal judges have put a hold on many of the Trump administration’s recent actions and orders at least temporarily. Some of these cases may end up with the Supreme Court.

The White House said it will appeal the court injunctions blocking their efforts, while also questioning the motives of the judges making those preliminary rulings.

“The real constitutional crisis is taking place in our judicial branch where district court judges in liberal districts across the country are using their power to unilaterally block the president’s basic executive authority,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt told reporters.

Vice President Vance suggested on social media that judges don’t have the authority to challenge President Trump’s “legitimate power.”

UCLA’s Emerson said the conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court has started to hem in Congress’ ability to oversee the executive branch.

“The post-Nixon reforms are under challenge, and may fall by the wayside,” said Emerson.

President Trump steps off of Air Force One at Palm Beach International Airport in West Palm Beach, Fla., on Feb. 14, 2025.

Roberto Schmidt/AFP

hide caption

toggle caption

Roberto Schmidt/AFP

The power of the purse

Another law under pressure is the Impoundment Control Act of 1974, a response to Nixon’s refusal to spend funds as directed by Congress. The law underscored that the Constitution gives Congress the power of the purse.

Trump officials have said the Impoundment Control Act is unconstitutional and are trying to move ahead with slashing spending on programs and agencies that don’t line up with the president’s policy priorities.

Some conservatives have said the Trump administration is stretching presidential power too far.

“I’d like to see a lot of agencies eliminated,” said Gene Healy, senior vice president for policy at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think-tank. “I don’t think an effort to do that is going to get very far without Congress.”

Congressional Republicans are standing by Trump

Healy said the post-Watergate era was really the last “serious sustained effort” by Congress to put the presidency back within its constitutional limits.

And other presidents have also tried new and different ways to exert their power, from George W. Bush’s wide-ranging actions after the Sept. 11 attacks, to Barack Obama’s actions protecting undocumented “Dreamers” brought to the United States as children, to Joe Biden’s push to erase billions of dollars in student loan debt.

“It didn’t start with Trump 1.0 and it didn’t stop during the Biden administration,” Healy said.

Today, a Republican-controlled Congress is showing much more deference to the White House as Trump tests the limits of his authority. Some congressional Republicans have introduced bills to give the president’s executive orders the force of law, while others have shrugged off questions about whether Trump has overstepped.

“The phrase I’ve been using for 20 years is, you can’t have an imperial president without an invisible Congress — and that’s certainly true today,” said Bowdoin College’s Rudalevige.

Newsportu’s Lexie Schapitl contributed to this story.

#Trumps #efforts #DOGE #cuts #test #Watergateera #reforms #Newsportu